AWEI Employee Survey Data Analysis

The AWEI Employee Survey, which accompanies the Australian Workplace Equality Index every year, is Australia’s richest source of annual and local data that focuses on both; LGBTQ inclusion initiatives and the impact of these initiatives on employees, regardless of how they identify. Participation in this optional employee survey has increased every year since it’s initial release.

To utilise this data, Pride in Diversity annually publishes a series of data materials, videos and blogs under the heading of AWEI PRACTICE POINTS.

2021 Practice Points

Edition 1: Key Insights

Published: 1 September 2021

The 2021 AWEI Employee Survey saw its largest response rate ever, with 45,000 participants across 186 organisations. While LGBTQ inclusion across the workplace continues to progress, there remains areas of concern where LGBTQ employees feel left behind. In this edition, we look at the perceptions and support from all respondents, and the lived experiences of LGBTQ people in the workplace.

Edition 2: Being Out at Work

Published: 8 September 2021

The data includes surprising and concerning findings on being out at work in regard to having a diverse sexual orientation. We focus on perceptions, engagement, safety, mental health and wellbeing, bullying and harassment, and a declining trend in respondents feeling comfortable enough to be out at work.

Edition 3: Bi+ Visibility

Published: 15 September 2021

This edition is planned in conjunction with Bi Visibility Day, an annual Diversity Day that celebrates the umbrella of Bi+ people and aims to bring awareness to the bi-phobia and bi-erasure this subset of the LGBTQ community faces. We dive into statistics that confirm what we already know and investigate areas of change to determine key actions.

Edition 4: Trans and Gender Diverse Inclusion

Published: 22 September 2021

In this edition, we look at two key areas. First, the general views and perceptions of all respondents regarding the inclusion of trans and gender diverse employees. Second, the focus on the lived experience of trans and gender diverse respondents, and the impact of inclusion initiatives on their wellbeing at work.

Edition 5: LGBTQ Women

Published: 6 October 2021

Pride in Diversity’s Sapphire Initiative promotes LGBTQ women and non-binary people perceived as women in the workplace. In this edition, we continue to investigate and understand the dual challenges for LGBTQ women; of being both a woman in the workplace and of diverse sexuality or gender.

Edition 6: Allies in the Workplace

Published: 13 October 2021

Being an Active Ally in the workplace is crucial to LGBTQ inclusion. We look at how respondents identify as an ally, how active they are as an ally, and reasons why they may not identify as an ally. We also look at the difference allies make to LGBTIQ employees and their overall sense of inclusion.

Edition 7: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

Published: 20 October 2021

One of our strategic initiatives is to take a deep look at intersectionality in the workplace and particularly those of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, for the purpose of understanding the unique experiences and challenges faced by LGBTQ First Nations people.

Edition 8: Regional Australia

Published: 27 October 2021

Another Pride in Diversity strategic initiative focuses on the regional or national reach across Australia. While we know that enormous strides have been made for LGBTQ employees around the country, there is still significant oversite regarding key messaging and support for those who live outside the major metropolitan areas.

AWEI 2021 Survey Insights

Written by Christopher Nelson, Senior Relationship Manager, Pride in Diversity | 7 December 2021

Response rate and respondents

There were 4,620 responses from the Resources industry or about 10% of the total 2021 responses.

47% of responses came from employees based in WA with the next highest in Queensland (21%). Most responses came from metropolitan areas (65%) and of those most were full-time employees (87%).

Most respondents were team members (42%) which is slightly higher than for all respondents. Expectedly, women made up 43% of Resources industry respondents as opposed to 54% for all respondents. There was little difference in rates of non-binary genders.

GLBTQ inclusivity within the Resources industry

The Resources responses gave a strong 81% agreement in supporting the work that their employer puts into LGBTQ inclusion, which is lower than the 85% recorded for all respondents. There was a similar difference in support recorded for thinking that this was an important space in which to be active.

In the Resources industry, 83% agree or strongly agree that there are visible signs of support for LGBTQ inclusion whereas only 78% of all respondents agree or strongly agree that there are visible signs of support.

Resources industry employees indicate that they understand some of the unique challenges that LGBTQ employees face in the workplace (81%) whereas 84% of all respondents are aware of these challenges.

The witnessing of negative behaviours is higher from Resources industry respondents at 18% compared to all respondents at 14%. Witnessing more serious bullying of LGBTQ employees is slightly higher in Resources industry at 7% vs 5% for all.

Allies for LGBTQ employees

There are fewer respondents in the Resources industry who identify as active allies for LGBTQ employees in the workplace (17%) as opposed to 20% for all respondents.

Active allies are slightly better known in the Resources industry (59%) compared to 56% overall, as were executive allies at 58% in Resources and only 54% across the board.

The highest reason for not being an ally in Resources and in all responses was that people were too busy (42% for both) although 25% of all respondents had no personal interest in LGBTQ inclusion, whereas this was higher in the Resources industry at 28%.

36% of Resources industry respondents would be influenced by a better understanding of how to be an active ally which is lower than respondents overall at 40%. 35% of Resources industry respondents said nothing would influence them to become an active ally; slightly higher than all respondents at 32%.

GLBTQ respondents

The Resources sindustry respondents were somewhat lower in their identification as LGBTQ at 15% as opposed to 19%.

A similar percentage of Resources respondents identify as gay or lesbian (53% vs 55%) as for all respondents, although 27% of Resources respondents identified as bisexual as opposed to 24% for all respondents.

On being out about sexual orientation in the workplace, Resources industry respondents are considerably less comfortable being out to all, at 33% compared to 41% for all respondents. Being out to a select few is higher with Resources respondents at 27% vs 21% for all respondents. Likewise, those not out at all is higher with Resources respondents (19%) compared to all respondents (16%).

24% of Resources industry respondents say that they have encountered exclusion based on their sexuality compared to 17% for all respondents, and over 20% of Resources respondents have been the target of unwanted jokes, innuendo, commentary as a direct result of their sexuality. This is considerably higher than the 13% reported by all respondents.

For those respondents not out at work, 40% say that they feel that being out would be detrimental to their workplace experience compared to 33% for all respondents.

Conclusions

The data from the participants in the resources industry is at the highest variance with respondents across all industry when it comes to being out at work or for having experienced actual exclusion, or derisive language in the workplace.

We certainly would need to contextualise the participation rates of survey respondents, as the relatively high number of respondents from metropolitan areas may be at odds with all employees typically assumed to be “resources workers”. Subject to validating the participation rates of those outside metropolitan areas, increasing participation in future surveys by those who are in regional areas or perhaps FIFO staff may help build a more comprehensive picture for this industry.

Written by Dawn Emsen-Hough, Director, ACON’s Pride Inclusion Programs | October 2021

Times are changing and so are we!

A Little History:

For the last 10 years Pride in Diversity has published an annual benchmarking report (based on the results of Australian Workplace Equality Index) and AWEI Employee Survey report.

In surveying a random but large cohort of our membership, our finding was that while members utilised extensively their own AWEI Survey Reports, the AWEI Practice Points and the Benchmarking Tables, little reference was given to the annual hard copy “master documents”. What came out loud and clear was the value of the data that we offer and our strong evidence base.

So, the following factors influenced our decision to change, a need to:

- Focus on what members clearly wanted – data, data, data and more of it!

- Be environmentally conscious through the reduction of printed publications – we can reach more people online and eliminate superfluous hard copies.

- Ramp up the AWEI Practice Points data sheets to extend the current ad-hoc data reporting to a multi-access system, providing:

- our members with greater value add regarding their own LGBTQ inclusion work; and

- non-members with an abridged version of what they need to know to progress their LGBTQ inclusion initiatives.

- Continue with the strong evidence base that is supported by current Australian data and research. Our data is annual, not several years old or US/UK based – this space changes quickly (and the data needs to be local!).

- Ramp up our academic alignment through partnerships with our academic advisors, the publishing of academic papers, and greater utilisation of the extraordinary data set which we produce annually.

- Continue to promote incredibly strong evidence on Australian LGBTQ inclusion by sharing the invaluable resource we produce – to inform both our practice and yours, inform media, those in our industry and our international partners.

Thank You, Goldman Sachs!

Goldman Sachs has been the sponsor of our annual AWEI Benchmarking and AWEI Employee Survey publications for the last ten years. When we approached the Goldman Sachs team with the idea of this new direction for the AWEI Practice Points, they were delighted. Goldman Sachs immediately acknowledged this as an essential step forward in remaining both current, innovative and the number one resource for LGBTQ workplace inclusion in Australia.

Goldman Sachs have committed to supporting our work in this area with the shift from the financial support of our two hard-copy publications to the financial support of our revamped AWEI Practice Points and all the new features that this will entail.

I would like to thank Goldman Sachs for their continued support of our work and in enabling us to extend our evidence base for our members, to the public and our international partners. On behalf of all us here at the Pride in Diversity team, Pride Inclusion Programs Division and ACON more broadly, we thank you!

So, what is going to change?

To determine the change needed, we needed to answer the following:

- How do we continue to add value to our membership with membership-only insights?

- How do we provide non-members, media and those working within inclusion insights outside of membership to extend the work and message of inclusion in Australia?

- How do we increase our alignment with universities, provide greater analysis of this rich source of data and publish more academic articles utilising the AWEI benchmarking results and employee survey data?

Our answer:

- Increase regularity of offerings in this space.

- Offer members exclusive access to Zoom training on each of the AWEI Practice Point topics – deep-dive insights with ongoing access to recorded content.

- Offer members exclusive access to raw, de-identified data (where relevant) as it pertains to the topic area being discussed.

- Make available to the public, international partners and media these published deep-dive insights (AWEI Practice Point data sheets) via our AWEI website and AWEI Practice Points mailing list.

- Increase our engagement with academic advisors, and contribute to academic articles and research utilising AWEI data.

So, this is what you’ll see:

- Pride in Diversity members, on request, will receive de-identified high level raw data that support the practice points that we are discussing enabling them to utilise data for comparison against their own Survey results.

- Newsletters … i.e., Our Practice Point data sheets will speak to the current data in regard to specific topics. Annually these insights will include:

- Key Findings

- Being out at work

- LGBTQ Allies in the Workplace

- Inclusion of Trans and Gender Diverse Employees

- Regional Reach

- LGBTQ Women

- Bullying & Harassment

- and more.

These will be available publicly via the Practice Points page on our PID-AWEI website and via our Practice Points mailing list. - Blogs – written by Director, Dawn Emsen-Hough highlighting discussion points around each of the deep dives will be available publicly, posted on LinkedIn and via our social media sites.

- Zoom training on each of the Practice Points data sheets/Newsletters available to members for live participation or via recording. The lock in this image identifies added value for Members only.

So, how do you make sure that you are on the receiving end of this data?

- If you are not a member, visit: Data Analysis | Australian Workplace Equality Index (pid-awei.com.au) or sign up to our AWEI Practice Points Mailing List (link available on the website, or click here). Non-members can also keep an eye out for our LinkedIn posts.

- If you are a Pride in Diversity member, the above applies.

- In addition, you can follow Pride in Diversity on LinkedIn in addition to requesting the password to recordings of our AWEI sessions.

- Members can also keep an eye out for our invitations to AWEI Practice Point Zoom training sessions.

- If you are from the Media: refer the first bullet point or contact ACON Pride Inclusion Programs Director Dawn Emsen-Hough for more information. You may also access our LGBTQ Inclusion Awards luncheon or Pride in Practice Conference if you intending to cover the event. Dawn can be reached on demsen-hough@acon.org.au or via her LinkedIn profile.

For more information on Pride in Diversity Membership, participation in the Australian Workplace Equality Index, AWEI Employee Survey or data analysis, please contact the Pride in Diversity Office on awei@prideindiversity.com.au.

written by Dawn Emsen-Hough, Director, ACON's Pride Inclusion Programs | 13 September 2021

Every year, Pride in Diversity facilitates the Australian Workplace Equality Index (AWEI), the national benchmark for LGBTQ workplace inclusion in Australia; and accompanying it, the largest annual employee survey that focuses specifically on the impact that LGBTQ inclusion initiatives have on employees working for organisations active in this area. This year 44,915 respondents participated in the survey. This blog seeks to identify, at a high level, why this area of D&I (Diversity & Inclusion) is benchmarked, why the single-focus surveys are valuable and how you can now gain greater access to its findings.

Why do we focus on just LGBTQ?

While we recognise that LGBTQ inclusion is only one area of an organisation's overall D&I strategy, it is the area that Pride in Diversity specialises in as the national not-for-profit employer support program for LGBTQ inclusion in Australia. There are numerous not-for-profits supporting employers in other aspects of D&I (such as disability, mature age, cultural diversity, RAP programs) each producing similar instruments and insights; each providing in-depth analysis within their areas of their expertise and focus. There are also some instruments that provide a high level, broad sweep analysis of D&I which can be beneficial but typically exclude the depth, challenges, views and/or inhibitors that are specific to a particular group within the population.

The AWEI benchmarking tool is a free tool open to all employers. The accompanying employee survey is open to all Pride in Diversity member organisations and those participating within the AWEI (membership not required for AWEI participation). While the benchmarking tool and accompanying survey provides a holistic approach to understanding the impact of your inclusion initiatives, each can be utilised independently. This combined collection of data provides a holistic analysis of the effectiveness of inclusion initiatives from both the business and employee perspective. Employers gain invaluable insights into the effectiveness and impact of their work in this area in addition to how these initiatives are perceived, valued and/or supported by their employees.

The impact of inclusion initiatives across the multi-faceted areas of diversity and inclusion have been positively outlined in academic and business papers alike, providing they are done correctly, not tokenistic and supported throughout the workplace culture.

The Australian Workplace Equality Index identifies a broad range of assessment areas that we know send a positive message of inclusion to LGBTQ employees while ensuring that policies and processes are not unintentionally discriminatory or exclusive in nature and most importantly, aligned with current discrimination law and best practice. The instruments look at the impact on workplace culture, the visibility of work in this area and the impact on both LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ employees alike. The instrument provides a very clear roadmap that employers can follow, covering not only the basic necessities for an LGBTQ inclusive culture but also areas that address current issues or roadblocks faced by people of diverse sexuality and/or gender. At times, it may focus on a particular demographic within the LGBTQ population to address areas of inequity that we know concerns not only the majority of employees within that demographic but also prospective employees looking to join the organisation. The index evolves as practice evolves and aligns itself not only with best practice here in Australia, but also diversity practice within business overseas. This is particularly important to global corporations, those who work international assignments and those managing talent programs that rotate staff between international offices.

Active vs Inactive Data Alignment

The rich source of data generated by the AWEI Employee Survey annually provides many employers with insight into the views of working Australians currently employed by organisations active in this space and while this data is useful, if your organisation is not participating in the survey, it's not YOUR data.

It is important to note that the information you get from a survey administered by an LGBTQ employer support program will be very different from a survey you administer internally. Internally administered surveys may miss significant areas of investigation, are typically high level and often do not tackle the nuances of a target population. Nor will internally administered surveys have the national response set against which you can benchmark each and every question. For example, the percentage of your LGBTQ employees who feel comfortable enough to be out at work becomes even more informative when compared to industry averages, groups, relevant sectors or the national average.

The same applies to the work you do in inclusion. This area of D&I is still evolving. It's not difficult to fall into the trap of looking at what you are doing and believing that it will suffice or meets employee and business expectations - but how does your work compare to that of your industry peers, competitors or ever-changing employee expectations.

Diversity initiatives do not represent fluffy HR rhetoric or merely focus on political correctness that some antagonists claim but rather tackle very real issues for business. We can cite corporate social responsibility but also need to keep in mind changing employee expectations, alignment with discrimination laws, employee value proposition, risk mitigation for people managers, the ability to attract and retain talent and the health, wellbeing, engagement and professional alignment of your staff.

Keeping on top of the data

We have for many years provided annual publications outlining industry and sector benchmarks for inclusion along with high level survey response stats. This information, summarised and completely de-identified has always been publicly available on our website (www.pid-awei.com.au) but has only typically been distributed to member organisations. Understanding the significance of 45,000+ responses annually, alongside benchmarked data on workplace policies and practices, we will shortly be launching Practice Points 2 which will not only provide much broader access to the data but will see us:

- regularly analysing key findings to determine the overall support for inclusion initiatives, the changing expectations of employees and the impact of initiatives on workplace culture

- focusing on particular areas of interest for example, those comfortable being out at work, the inclusiveness of a workplace culture, LGBTQ women, visibility of inclusion initiatives, regional reach; expectations of graduates and leadership

- Using this information to determine the impact of work on both supportive and non-supportive employees alike, those who identify as LGBTQ and those who do not;

- Providing greater visibility of what still needs to be an area of focus, what is working well and what we can do better

In addition to:

- providing raw, de-identified data for inclusion in academic papers;

- engaging with academics for a more active academic scrutiny of our findings;

- partnering with universities in joint research projects/publications.

While we will be extending and promoting widely the data that will be publicly available to all D&I practitioners, executive sponsors, network leads, media and/or interested parties, members of Pride in Diversity will also enjoy additional benefits with easily accessible training in each of the focus areas and access to de-identified, high level, raw response sets that can be utilised within internal data programs to benchmark against their own data.

To be kept up to date with the Australian data set on LGBTQ workplace inclusion or for more information on the benchmarking and survey instruments, please visit www.pid-awei.com.au. Alternatively you can receive all data updates by joining our Practice Points Mailing Lists by clicking here.

We look forward to launching Practice Points 2 in the coming months.

written by Brett Atkinson, Senior Relationship Manager, Pride in Diversity | 4 August 2021

written by Brett Atkinson, Senior Relationship Manager, Pride in Diversity | 4 August 2021

Introduction

The 2021 AWEI staff survey marked a year of considerable disruption. Amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, its economic fallout, and the ensuing retreat into our houses during lockdowns, organisations not only continued to participate in the AWEI benchmarking and survey, but also participation rates reached a new peak. AWEI 2021 saw a total of 161 submissions, and the survey recorded 44,915 respondents, a remarkable increase of nearly 34% from the previous year.

The data this year show a consistent positive link between inclusion in the workplace and employee general well-being. We have all seen anecdotal evidence that companies can actually generate returns for their shareholders or value for their stakeholders when they strive to achieve best practice in diversity and inclusion (“D&I”). But no matter the company or industry type, there is a reluctance to dive in headfirst, with many having to balance the needs and sensitivities of a broad employee base.

The AWEI benchmarking tool attempts to measure the LGBTQ+ inclusivity of workplace policies and practices, while the survey measures the results or impact of such policies and practices. Now in its 11th year, the survey has matured to include more in-depth indicators of inclusion and reflects the rapidly changing behaviours and attitudes of society. The information below is relevant for the Higher Education sector.

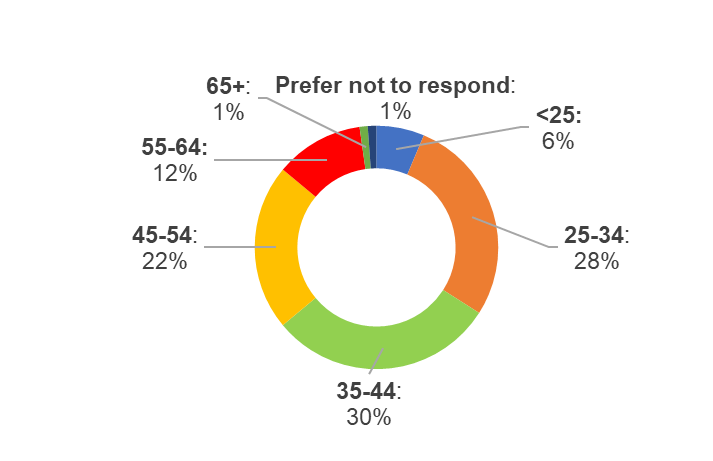

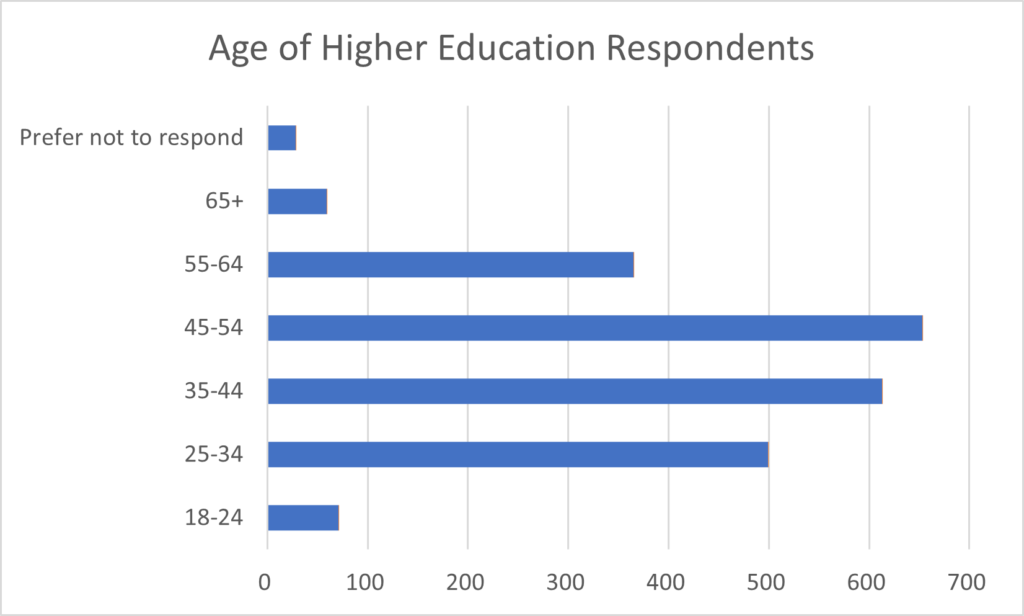

Age of Respondents

Response rates and respondents

The 2021 survey saw a lower response rate compared to the previous year with 2288 compared with 2902 in 2020. The locations of respondents vary with the majority of people coming from NSW (36.67%) and WA (35.45%). There has been a significant shift from the 2020 survey relating to Victoria with only 13.46% of people completing the survey from this state compared to 36.13% in 2020.

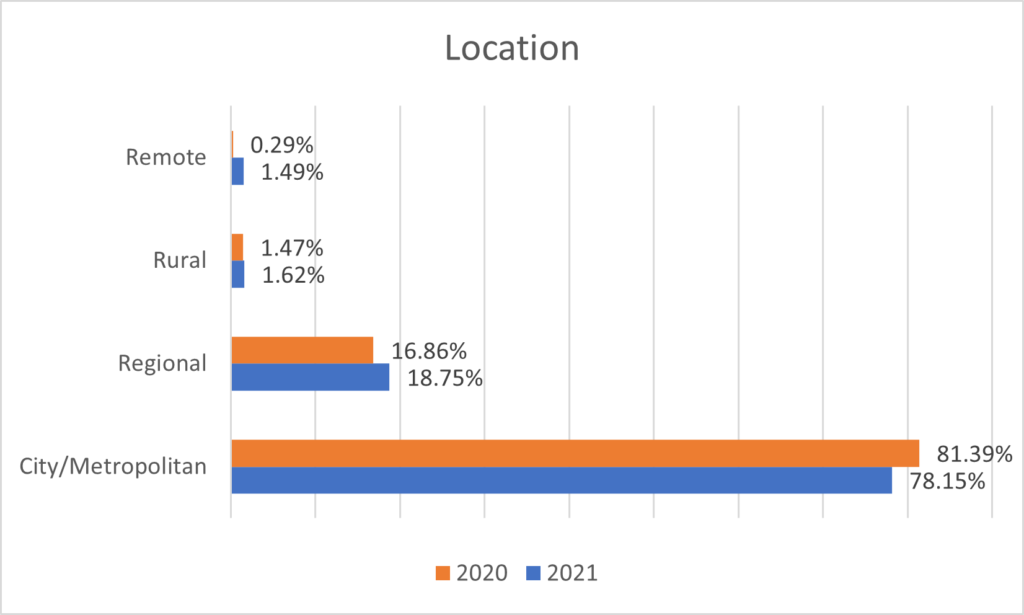

In relation to the location of where people are employed who completed the survey, there is a slight shift to Regional from City/Metropolitan.

GLBTQ inclusivity within the Higher Education sector

When completing the survey, we ask people to consider their personal views when it comes to the inclusion of sexuality, and gender diverse people. In this cohort of people, 86% of people personally support the work their organisation does for the inclusion of employees, which is similar to all respondents, in which 85% say they also support the work they do across all sectors.

However, 51% of people in Higher Education believe their organisation should put more effort into this aspect of Diversity and Inclusion compared to the national survey of 42%.

When asked about jokes and innuendo being acceptable in the workplace and being called out or addressed in the workplace, there is no significant difference between the Higher Education sector compared to all respondents.

In relation to Awareness or Ally training being made available to people throughout the year, 73% strongly agreed or agreed this was the case compared to 59% for all respondents.

When it comes to Allies, 68% of respondents in Higher Education know of active allies in their immediate work area compared to only 56% from all respondents. Yet there are not considerable differences when it comes to people knowing of executive allies or sponsors within my organisation (56% vs 54%). The common response as to why people are not active allies are people saying they are too busy (45%), but 50% of people said having more information on being an active ally when my time is limited, would influence them to become and active ally.

The inclusivity of the Higher Education sector relating to trans and gender diverse communities, we see higher levels of acceptance relating to gender neutral or all gender bathrooms. Compared to the national survey, Higher Education are more comfortable having all gender toilets on their floor (assuming male and female toilets are still available) 87% vs 79%, and more comfortable if all toilets were changed to all gender on our floor 56% vs 45%.

GLBTQ respondents

In relation to sexual orientation, less people identified as Gay/Lesbian (51%) compared to other sectors (54%). Higher Education experiences lower forms of bullying and harassment compared to the national survey and also being the target of unwanted jokes, innuendo and commentary as a direct result of my sexuality. Workplace inclusion initiatives for diversity of sexuality and gender have had a positive impact on how I feel about my own sexuality are slightly lower for this sector compared to the national AWEI data 56% vs 60%. For the Higher Education sector there is a decline from 2020 in the number of people who are out to everyone.

Conclusions

The survey results compare similar for the Higher Education sector compared to the survey results from all respondents across most of the questions. Like other sectors, there needs to be more work promoting the need for active allies in the workplace, and building on executive allies. There needs to be more work done in relation to people feeling they can bring their whole selves to work as this area is lower than the national responses (36% vs 41%).

written by Christopher Nelson, Senior Relationship Manager, Pride in Diversity | 22 July 2021

Response rate and respondents

There were 1,549 responses from the retail sector or about 3% of the total responses. Considering the number of employees in Pride in Diversity’s retail members, this is a very small proportion.

42% of responses came form employees based in NSW with the next highest in Victoria (24%). The vast majority of responses came from metropolitan areas (88%) and of those most were full-time employees (71%).

Most respondents were team members (41%) which is equivalent to all respondents, although a higher number of respondents were in leadership roles. The age demographic of retail respondents was, understandably lower. Those aged under 18 years of age were 11% compared to only 5% of all respondents. Those aged 45 and above made up only 24% of retail respondents but 40% of all respondents. Expectedly, women made up 59% of retail respondents as opposed to only 54% of all respondents. There was little difference in rates of non-binary genders.

GLBTQ inclusivity within Retail

The Retail responses gave an overwhelming 90% affirmation in supporting the work that their employer puts into LGBTQ inclusion, which is higher than the 85% recorded for all respondents. There was a similar difference in support recorded for thinking that this was an important space in which to be active.

Likewise, there are more visible signs of support for LGBTQ inclusion in retail employers (84% agree or strongly agree) whereas only 78% of all respondents agree or strongly agree that there are visible signs of support.

Retail employees indicate that they understand some of the unique challenges that LGBTQ employees face in the workplace (89%) whereas only 84% of all respondents are aware of these challenges.

There is little difference between the Retail sector and all respondents in the witnessing, prevalence and addressing of LGBTQ jokes/innuendo and more serious bullying and harassment, however the Retail sector is better on all scores.

Allies for LGBTQ employees

There are more respondents in the Retail sector who identify as active allies for LGBTQ employees in the workplace (24%) as opposed to 20% for all respondents. LGBTQ respondents in the Retail sector are more likely to be active allies for others in their community (58%) than all LGBTQ respondents at 51%.

Active allies are better known in the Retail sector (63%) compared to 56% overall, but executive allies are less well recognised at 51% in Retail and 54% across the board.

The highest reason for not being an ally in Retail and in all responses was that people were too busy (38% in retail and 42% for all) although 25% of all respondents had no personal interest in LGBTQ inclusion, whereas only 20% indicated that in the Retail sector.

48% of Retail sector respondents would be influenced by a better understanding of how to be an active ally as opposed to only 40% of respondents overall. Only 26% of Retail sector respondents said nothing would influence them to become an active ally; thankfully much lower than all respondents at 32%.

GLBTQ respondents

The retail sector respondents were higher in their identification as LGBTQ at 24% as opposed to 19%, which is significant.

A higher percentage of Retail respondents identify as gay or lesbian (65% vs 55%) as for all respondents.

On being out about sexual orientation in the workplace, Retail sector respondents are considerably more comfortable being out to all, at 53% compared to 41% for all respondents. 90% of Retail sector respondents say that they have not encountered any exclusion based on their sexuality compared to 83% for all respondents.

For those respondents not out at work, 53% say that they feel that they would not be accepted by their colleagues (39% for all respondents) and 41% say that they are not comfortable within themselves to out at work, compared to 38% for all.

In terms of the impact of active allies, 60% of LBTQ retail respondents indicate that there has been a positive impact on their sense of inclusion compared to only 49% for all respondents. There are fewer Retail respondents identifying as bisexual than overall (17% vs 24%).

Conclusions

We need to encourage greater participation by employees in the retail sector in the AWEI. Low participation rates make drawing strong conclusions from the data difficult.

The fact that most retail respondents were based in metropolitan centres (88% vs 82% for all), may indicate that the survey is yet to penetrate the regional and rural retail shopping centres and stores. It would be desirable to see the regional, rural and remote participation rate of respondents increase over time, to include more workers on the shop floor, rather than office locations.

More work needs to be done across the board to turn passive allies into active ones, which means more education on why allies are important and how people can be active allies while having busy jobs. Senior leaders have an important role in this by speaking publicly with their own ally stories.

Although the Retail sector rates higher than the average on being out at work, if you are sexually diverse, the fact that more young and new employees feel unable to be themselves in the workplace requires greater visibility of LGBTQ inclusion. The assumption is that people of a younger age demographic will explore and come to terms with their sexual and gender diversity. The younger age demographic of retail employees makes the role that retail employers have more significant in promoting and normalising LGBTQ inclusion.

written by Jess Mayers, Senior Relationship Manager, Co-Convener Sapphire Programme, Pride in Diversity | 9 July 2021

The 2021 engagement survey saw over 2,200 survey respondents from organisations within the Professional Services & Consulting sector (PS&C). The analysis does not include those professionals employed in other sectors. Of these, 401 participants identified as being part of the LGBTQ community (17.75% vs 18.8% of the national cohort).

Demographics

Regarding the demographic segmentation of the survey participants, this sector differs from the national mix in several significant areas:

- Has more representation of men (49.49% PS&C vs 43.13% nationally), and less of women and non-binary people (48.34% vs 54.22% and 1.06% vs 1.25% respectively)

- Has more employees with bachelor and post-graduate degrees (84.73% vs 63.77%)

- Over-represented by people working in city/metro areas (91.54% vs 81.13%)

- Over-represented by people in senior management positions (13.7% vs 7.5%)

- The sector also appears to be under-represented by:

- Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders (0.67% vs 2.44%)

- People living with disabilities (2.84% vs 4.55%)

- Neurodiverse people (2.84% vs 3.97%)

- Mature age employees (11.14% vs 16.19%)

General Populations View on LGBTQ Inclusion

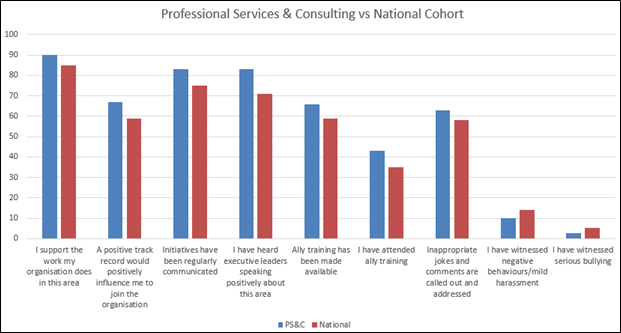

When looking the work organisations are doing in this area and how the workforce views those initiatives, the responses of PS&C employees tracked ahead of the national response.

There is broad support for the work being done by PS&C organisations, and overall, there seems to be good communication plans in place, both generally and from executives.

While responses about training do track better than the national response, there is still work to be done in offering training, and then in the promotion of sessions and in giving employees the freedom to attend during work hours.

Health & Wellbeing

Health and wellbeing indicators were equally to or slightly higher than average:

- 80% of respondents feel mentally well at work (vs 78%)

- 86% feel they can be themselves at work (vs 81%)

- 80% feel a sense of belonging (vs 77%)

Business case indicators were also on par with 90% of participants feeling productive (vs 88%) and 83% feeling engaged (vs 81%).

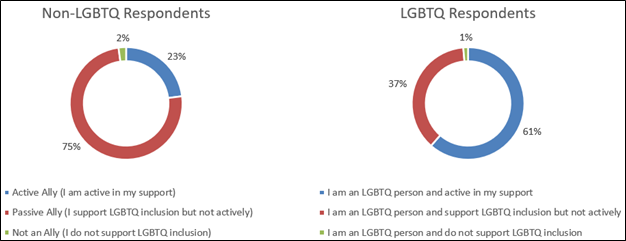

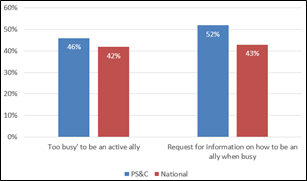

Active Allies

When it comes to active allies, the sector matches the national profile, with 29% of total respondents describing themselves as active allies, compared to 28% nationally. LGBTQ people are almost three times as likely to be an active ally than non-LGBTQ respondents.

Allies are more visible within PS&C than the national cohort, with 63% of respondents saying they know of allies within their work area (56% nationally). Executive allies are also more visible, with 67% of PS&C respondents knowing of active exec’s compared to just 54% nationally.

For people who support LGBTQ inclusion but are not active, the main reason given was ‘too busy’. The provision of information on being an active ally when time is limited is likely to be far more influential in this sector.

For people who support LGBTQ inclusion but are not active, the main reason given was ‘too busy’. The provision of information on being an active ally when time is limited is likely to be far more influential in this sector.

This is an important group of people, and potentially means many can be ‘activated’ with the provision of targeted education/resources.

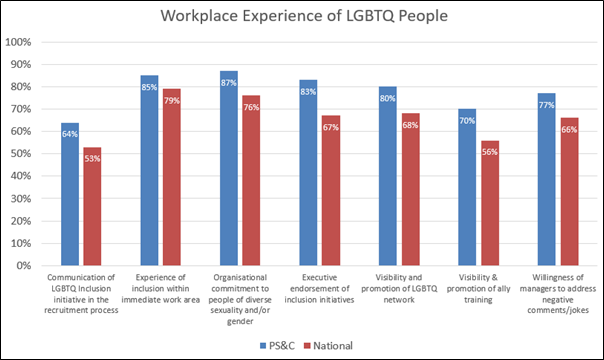

Workplace Experience of LGBTQ People

The experiences of LGBTQ employees participating in the survey from the professional services and consulting sector is more positive than the national cohort across the board, with organisations meeting or exceeding their expectations in every area asked about.

It is pleasing to see that, for LGBTQ employees, visibility of active allies is higher than the national cohort (71% vs 57%), and in turn, the visibility of active allies has positively impacted their sense of inclusion (64% vs 49%).

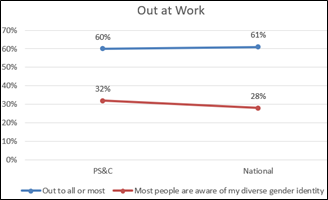

However, despite the seemingly more positive experiences, LGBTQ employees within PS&C report similar levels of being ‘out’ in their workplaces as the national cohort.

It is worth noting for people with a diverse sexuality, the number of people who are completely out in the workplace has been decreasing since 2019.

It is worth noting for people with a diverse sexuality, the number of people who are completely out in the workplace has been decreasing since 2019.

Again, the experiences of those employees with a diverse sexuality who are out in the workplace are reported as being better in the PS&C sector compared to the national cohort:

- I would feel supported by my organisation to come out to suppliers, customers, or external business contacts (84% vs 78%)

- I have not encountered any exclusion based on my sexuality within the organisation (91% vs 83%)

- My sexuality would not have any impact on my career progression (86% vs 81%)

- My performance is positively impacted by being out (80% vs 66%)

- My overall engagement is positively impacted by being out (86% vs 73%)

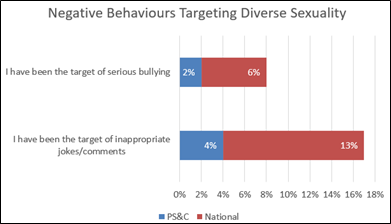

When comparing negative behaviours, employees with a diverse sexuality who are out in the workplace experience both inappropriate jokes and comments, and more serious bullying at lower rates than the same cohort at the national level.

When comparing negative behaviours, employees with a diverse sexuality who are out in the workplace experience both inappropriate jokes and comments, and more serious bullying at lower rates than the same cohort at the national level.

One of the more significant variations from the national indicators was whether workplace inclusion initiatives (for diversity of sexuality and gender) have had a positive impact on how they felt about their sexuality. 82% agreed on this point, whereas nationally only 60% did.

Regarding not being ‘out’, the reasons why tended to be similar to the national cohort. The main reasons given were:

- Not comfortable within myself to be out at work (39% of both this sector and the national cohort)

- I do not feel I would be accepted by some members of my team (29% PS&C vs 39% national cohort)

- Being out at work would be detrimental to my workplace experience (25% vs 33%)

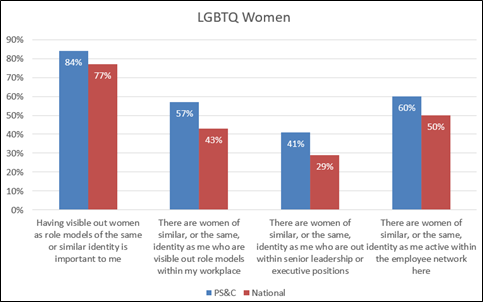

LGBTQ Women

While the results of LGBTQ women working in the PS&C sector again track ahead of the national cohort, there is still a gap between women looking for a role model, and seeing LGBTQ women acting as out, visible role models and within leadership positions.

Trans and Gender Diverse Inclusion

Encouragingly, 72% of gender diverse employees in this sector saw visible organisational inclusion for gender diverse employees (vs 58%), but some practical measures, while better than the overall national results, indicate support for trans and gender diverse employees is still lagging:

- 53% of respondents reported they had freedom to use toilets of choice (vs 42%)

- 48% reported some alternatives to gendered dress codes or uniforms (vs 41%)

- 52% report their organisation acknowledges gender diversity beyond the binary of male/female (vs 47%)

Almost all areas looking at the experiences of TGD employees show that their experience overall is poorer than that of employees with a diverse sexuality.

This includes 1.2% of people being deliberately misgendered, 6% of people being targeted with unwanted jokes, innuendo, commentary as a direct result of their gender diversity, and 4% being the target of more serious bullying/sexual harassment ( vs 8%, 8% and 6% respectively).

- 65% can freely use gendered toilets of choice without opposition (vs 49%)

- 65% report people make an effort to use their personal pronouns (vs 58%)

- 76% have not experienced any exclusion based on their gender diversity (vs 66%)

- 73% report their gender identity has not had any impact on their career progression (vs 64%)

- 75% say workplace Inclusion initiatives for diversity of sexuality and gender have had a positive impact on how they feel about their own gender diversity (vs 56%)

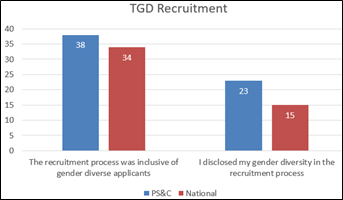

The data around recruitment also shows there is still some work to be done in this area. While the process felt slightly more inclusive for applicants in the PS&C sector, the percentage of applicants that found it inclusive was still low, and so this should be a focus for organisations in the future.

The data around recruitment also shows there is still some work to be done in this area. While the process felt slightly more inclusive for applicants in the PS&C sector, the percentage of applicants that found it inclusive was still low, and so this should be a focus for organisations in the future.

Regional Inclusion

While there are few regionally/rurally based employees within this sector, those who are report higher levels of inclusion than the national cohort. For example, 68% report their organisation's diversity initiatives for the inclusion of people of diverse sexualities or genders have been adequately communicated within their site/office (vs 59%), 61% report being easily able to connect into head office activities for this area of diversity & inclusion (vs 46%), 45% report having a local person/champion to help drive sexuality and gender diversity inclusion initiatives (vs 35%).

Summary

Overall, the Professional Services & Consulting sector tracked well ahead in any areas than the national cohort. Communication, visibility, and exec endorsement all ranked highly amongst the LGBTQ cohort, and there seemed to be broad understanding and support from the total PS&C cohort for the work being done.

Areas that should be focused on are the provision of training, including the promotion of and encouragement to attend, inclusion for trans and gender diverse employees and recruitment applicants, and increasing the presence and visibility of LGBTQ women. While the majority of employees work in metropolitan areas, the support of regional employees should also be a focus of future strategies.

written by Mark Latchford, Associate Director, Pride in Diversity | 6 July 2021

The Australian legal firms were early engagers in LGBTQ specific inclusion initiatives within their workplaces and this is reflected with a generally positive analysis from the AWEI in 2021. From the perspective of their LGBTQ employees, their allies and the wider workforce, the organisations collectively seen to be doing a more positive job than the national survey cohort. Nevertheless, the preparedness to be out to everyone or most has seen a significant year-to-year decline in the legal sector. Moreover, for attracting and retaining gender diverse talent, there is particular work still to be undertaken, based on what can be seen from the survey.

Demographics

Nearly two thousand members of the legal sector participated in this year’s survey, which was nearly exactly the same number who participated in 2020 (although the total national participation increased by over eleven thousand to nearly forty-five thousand). 43% of the legal fraternity indicated they had participated in the previous survey.

Not unexpectantly, the sector was over-represented with those resident in NSW and Victoria and under-represented from those from the smaller states, especially Western and South Australia. The location of the respondents was heavily skewed to metropolitan locations. Interestingly, 15.1% indicated they worked part-time, which compares to only 10% of the national cohort.

The legal community who were surveyed tended to be relatively newer employees to their current organisation (48% had worked less than three years at their current employer as compared to 34% of the national response). This was also reflected in the relative youth of those surveyed with 9% under 24 years of age and 39% between 25-34, while the national cohort recorded 5.3% and 24.5% in these age ranges. Conversely, older people (ie 45 years and beyond) made up 24.8% of the legal sector as opposed to 40% nationally.

Significantly, the legal sector participation was skewed to women who represented 67% of the respondents (whereas that number was 54% nationally). The national and legal sector percentages who indicated there were of diverse sexuality or diverse gender were similar (18.8% nationally and 17.9% in legal).

Legal sector participants claimed to be more senior than average (for example, 11% claimed to be in senior leadership and/or CEO or reporting to CEO, compared to 7% nationwide). As you would expect, the legal sector is well represented with those with higher levels of education (with 41% having a bachelor degree (32% nationally) and 24% with postgrad degrees (22% nationally).

Finally, the sector was better represented than the national cohort with people of colour; and people with a culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) background but underrepresented by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders; people living with a disability; people who are neuro-diverse and also mature age employees.

The wider employee community and their responses

Overall, the wider legal community in the workforce appears to have a more progressive point of view about LGBTQ inclusion. For example, 91% of these respondents felt that romantic relationships were just any other and 63% believed there was more than two genders (By comparison, these numbers were 87.7% nationally and 54.6% nationally). Critically, the wider population (70%) felt an organisation’s track record in this aspect of inclusion would positively influence them to join an organisation. (In the wider population, that number was lower at 59%). Moreover, 91% felt work in this aspect of diversity and inclusion had a positive influence on organizational culture, nine points above the national percentage believing the same thing.

Seeing the focus on inclusion; understanding of why this work was being done; communication of initiatives, including visible signs around LGBTQ inclusion; availability of information and others indicators showed significantly better results in the legal sector than the national average. Of particular note is a very high (82.6%) acknowledge that executives in legal firms spoke positively about LGBTQ inclusion (compared to only 70.5% nationally).

Availability of awareness or ally training was noted by nearly 76% of the legal community (only 59% nationally) and nearly 46% has attended such training (as opposed to only 35% nationally).

This group also confirmed inappropriate language was not acceptable (96%) but only 61% thought it would be called out or addressed. Comfort with using different names and pronouns post a colleague’s affirmation was high at 94% (vs 88% nationally) as was the comfort with having ‘all-gender’ bathrooms on the floor (85% vs 79% nationally). It one of the few areas where the legal sector’s position was (marginally) lower than the national cohort, was on the question of all toilets being ‘all-gender’. 44.8% were comfortable with that idea vs 45.2% nationally.

Finally, the willingness to be an active ally in the legal sector was a positive 27% (as opposed to only 197% nationally and those not supporting LGBTQ inclusion and therefore not an ally was a small 1.2% (over half the national number). The knowledge of active allies in the immediate work area was particularly strong at 76% (whereas the national number was only 56%). This corresponded with deeper knowledge about being an ally including understanding why allyship is important, knowing behaviours expected and also the location of resources. Visibility of active executive allies was particular strong in the legal sector at 76% (vs nationally 54%). When asked why there were not allies, workload dominated the reasoning at 46% (and only 4% saw a conflict with their beliefs or values whereas 9% of the national cohort had that conflict).

Inappropriate workplace behaviours

Of the wider employee community within legal, 10% had witnessed negative behaviours and mild harassment (lower than the national 14.3%) and 2.5% had witnessed more serious bullying of those with diverse sexuality or diverse genders.

The Business Case and the Wellbeing Case

The 2021 survey confirmed the value of inclusion work. 91% of legal respondents indicated they felt productive at work and 85.6% felt engaged at work, because of these initiatives (both indices higher than the national percentage). 93.5% felt safe and included at work and 81% felt mentally well at work. 85.8% felt they could be myself at work which compared to 80.8% nationally.

Meeting Expectations

As with other indicators, legal sector employers are fairing better than other sectors, in meeting expectations of the LGBTQ talent they seek to recruit or retain. When asked about the inclusion experience within the LGBTQ employees immediate work area, near 88% said their expectations were met or exceeded (78.5% nationally). Organizational commitment to inclusion for diverse orientation and diverse gender was rated at 84%, nine points above the national data point. Other areas looked at including communication, both during the recruitment process and ongoing; executive endorsement for inclusion; visibility and promotion of LGBTQ networks and willingness for managers to address negative commentary were on average, ten points above the national average. The visibility of active allies was assessed at a strong 73% (nationally only 57%) and also visibility of allied training at 76% vs 56% of the national feedback, indicated the systemic approach many legal firms have taken on taking the conversation forward is resonating. The value of this approach can also be seen in the fact that 65% felt Active Allies had positive impacted LGBTQ employee sense of inclusion (49% nationally) and that about 84% said they did not here jokes or innuendo in their workplace, relating to either sexual diversity or diverse genders.

Degree of Outness

The 2021 AWEI data suggests that despite the many better than average indicators referred to above, the degree of ‘outness’ in the workplace is similar to the national status. 42% of legal employees were out to everyone (40.54% nationally) and a further 18.5% out to most (20.1% nationally). 14.6% were not out at all (marginally less than the national figure of 15.9%).

However, there has been a negative movement in these indicators’ year-to-year. In 2020, 44.4% of legal employees were out to all and 22.6% out to most, so 67% generally out. This year, that indicators has dropped to 60.5% out to all or most, a significant year-to-year decline.

Despite this sobering news, other indicators confirm the value of being out. 92% feel their sexuality has not impacted their career progression (83% of the national cohort felt the same way) and 80.4% felt their performance had been positively impacted by being out at work (versus 65.7% nationally).

The degree that legal employees had been the target of unwanted jokes, innuendo and commentary was half the national rate (6.5% vs 12.7% which is similar to 2020 at 6.6%) and those who had been the target of more serious bullying and sexual harassment (based on their sexuality) was also over half the national rate at 2.4% (vs 5.6%). This is very positive movement from the 5% in 2020.

When those not out at work were asked, why not?, the main reasons where ‘I feel I would not be accepted by some members of my team’ (32.3%); ‘I am not comfortable enough myself to be out at work’ (28.3%) or ‘I feel being out work would be detrimental to my workplace experience’. This confirms the value of positive story-telling by members of the LGBTQ community within legal firms and communicating across the entire organisation, so as to reach out to those who are hesitant.

Focusing on Gender Diverse

It is primarily in the area of gender diverse talent that the legal sector is sometimes below the national average team members. 60 professionals in the legal sector participated in this part of the survey. This was particularly the case during the recruitment process when only 28% felt application forms were inclusive (36% nationally) and support contact persons were identified by 8.7% (9.5% nationally). 10.3% of this cohort still had fears of being discriminated at work because of their gender identity (as opposed to 23.06% nationally) which is still too high. Only 7% held a fear of being outed for their gender diversity, during the recruitment process whereas 13% felt the same way national).

Although visibility of gender diverse inclusion work was relatively strong in the legal sector (65.6% vs 58% nationally), the freedom to use toilets of choice (36%), availability of all gender toilets (18%) and the freedom to use gendered toilets without opposition (10%) were all well below the national indicators (n: 42%, 28%, 24% respectively).

A relative low number of gender diverse legal respondents (11.8% as opposed to 28.1% nationally) indicated that most people at work were away of their gender diversity yet only 12% said people made the effort to use the right personal pronouns (27% nationally). As such, only 27.4% felt fully supported by their teams in terms of their gender identity (35.6% of the national cohort said the same thing) and only 6% felt happy with the gender affirmation process undertaken within the workplace (well below the 26% feeling the same way nationally).

On the positive side being the target of unwanted commentary because of their gender identity was a low 2% (nationally 8.4%) as was being the target of more serious bullying at 4% (5.6% nationally). was low at 2%. However, only 29% felt safe and supported such harassment (versus 45% of the national gender diverse cohort).

Intersectionality in the Workplace

Despite strong participation by women in the AWEI survey from within the legal sector, the gender challenge within the industry was evident in a number of responses. The visibility of women role models for example was at 42.5% (slightly below the national 43.5%) yet having such role models was seen as important to nearly 82% of respondents. The good news is that legal employee networks are seen as being inclusive of women of diverse sexuality and/or gender by 77% (nationally only 68%).

Regional and rural based employees in the legal sector generally felt more positively about the state of inclusion (when compared with the national response) and in particular, they felt easily connected into head office activities (60% versus 46% nationally). A compliment to the communication strategies implemented by the firms.

Finally, those employees of colour or identify as culturally and linguistically diverse feel most accepted within legal sector organisations, whereas those persons of faith feel least accepted in the workplace. Food for thought in regard to a holistic approach to inclusion in the workforce.

written by Adrian F., Senior Relationship Manager, Pride in Diversity | 5 July 2021

Introduction

This year’s survey marked a year of massive disruption. Amidst the tragic Covid-19 pandemic, its economic fallout, and the ensuing retreat into our houses during lockdowns, organisations not only continued to participate in the AWEI benchmarking and survey, but also participation rates reached a new peak. AWEI 2021 saw a total of 161 submissions, and the survey recorded 44,915 respondents, a remarkable increase of nearly 34% from the previous year.

The data this year show a consistent positive link between inclusion in the workplace and employee general well-being. We have all seen anecdotal evidence that companies can actually generate returns for their shareholders or value for their stakeholders when they strive to achieve best practice in diversity and inclusion (“D&I”). But no matter the company type, there is a reluctance to dive in headfirst, with many having to balance the needs and sensitivities of a broad employee base.

D&I is wide and amorphous, and LGBTQ+ inclusion, covering broad population types, can notoriously be hard to define. Because of this, the AWEI benchmarking tool attempts to measure the LGBTQ+ inclusivity of workplace policies and practices, while the survey measures the results or impact of such policies and practices. Now in its 11th year, the survey has matured to include more in-depth indicators of inclusion and reflects the rapidly changing behaviours and attitudes of society. We hope that this analysis will sharpen the focus on areas where engineering companies can do more to support their employees to bring their whole selves to work.

Response rate and respondents

Figure 1: Age of Engineering respondents

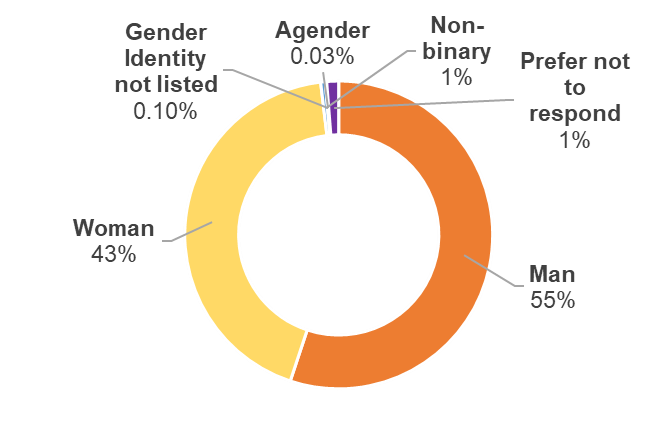

Figure 2: Gender Identity of Engineering respondents

There were 3,041 respondents from the engineering industry this year, with the majority (32%) of respondents working in Western Australia, followed by 25% in New South Wales and 17% in Queensland. This contrasts with the overall respondents who mostly work in New South Wales (30%), Victoria (22%) and Queensland (15%). A large majority of respondents from the engineering industry work in the private sector (93%) compared to the overall number of 45%. Nearly half of engineering respondents were also team members or team leaders/supervisors (46%) with numbers tapering off as roles become more senior or junior, which is consistent with the overall respondent trend. Unsurprisingly, there were more respondents who identified as men (55%) in the engineering industry compared with the overall figure of 43%, and 43% of engineering respondents identified as women compared to the overall 54% figure (Figure 2).

LGBTQ+ Inclusivity

As many engineering respondents as overall respondents (~85%) support the work of their organisation does for the inclusion of employees with diverse sexualities and genders. Likewise, around 81% of engineering respondents think that it is important that employers be active in the area of LGBTQ inclusion, compared to the overall figure of 83%.

Visible Signs. 80% of engineering respondents were more likely to have heard a senior executive speak about LGBTQ inclusion, compared with 70% in the overall population. They were also slightly more likely (82%) to have seen visible signs of support in the workplace than overall (78%).

Jokes and innuendo. When asked about jokes and innuendo targeting LGBTQ+ people, similar numbers of engineering respondents (~92%) to the overall population agreed that they are not acceptable in the workplace, and 58% agreed that they would be quickly addressed.

Allies. When it came to allies, many more engineering respondents said that they were passive allies (75%) compared to 70% in the overall population. Fewer people said that they were active allies (21%) in contrast to the 28% overall. When asked to consider what would influence them in becoming an active ally, engineering respondents were roughly in line with overall respondents with around 40% of them wanting to know how to be active allies, and around 45% of them wanting more information on being active with limited time.

Employer inclusion practices. Engineering respondents of diverse sexuality and gender were also more satisfied with their employer when it came to employer inclusion practices in the workplace. They were more likely than the overall population to report that their employer exceeded or met expectations in the following key areas:

- Experience of inclusion

- Communication of inclusion

- Level of executive endorsement

- Visibility and promotion of employee network and allies

- Visibility of active allies

However, respondents of diverse sexuality and gender in engineering were as likely as the overall population to report that they:

- Feel comfortable bringing my partner to work events here

- Recommend this organisation as an inclusive place to work for people of the same, or similar, sexual orientation and/or gender diversity

- Do not hear jokes/innuendo targeting people of diverse sexuality and gender here

- Any jokes/innuendo targeting people of diverse sexuality and/or gender are acted upon quickly here

- Active Allies have positively impacted my sense of inclusion here

LGBTQ+ respondents

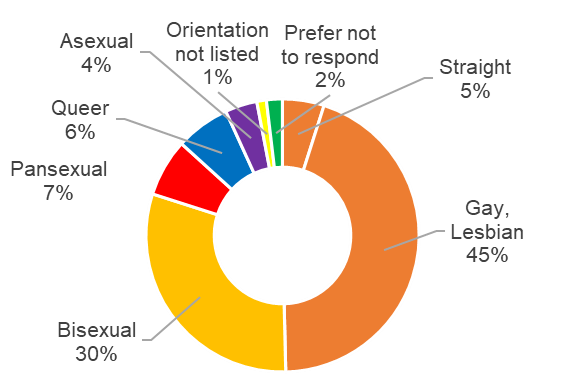

Figure 3: Sexual orientation of Engineering LGBTQ+ respondents

Perhaps unexpectedly, there were fewer engineering respondents (45%) who identified as Gay or Lesbian in contrast with the overall population figure of 55%. There were then more engineering respondents who identified as Bisexual (30%).

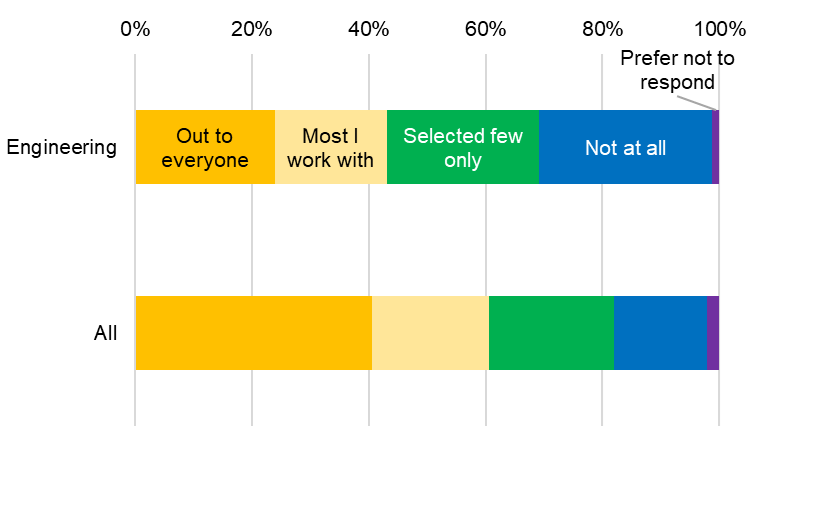

Figure 4: Proportion of people out at work

Being Out. When asked about being out at work regarding their sexual orientation, disappointingly far fewer people in the engineering industry report being out to everyone. Only 24% of engineering LGBTQ+ respondents say that they are out to everyone, compared to 41% in the overall population. They are also much more likely not to be out at all (30%) compared to 16% in the overall population.

Those who report being out at work still report being the target of jokes and innuendo because of their sexuality (~12%) both in engineering and in all respondents. However, a substantial proportion of engineering respondents who are out at work say that they will feel safe and supported reporting bullying and harassment to HR (92%) compared to 81% in the overall population.

Not Being Out. The top three rated reasons for not being out in the workplace in the engineering industry were:

- Not comfortable enough within myself (41%)

- Not feel I would be accepted (28%)

- Being out at work will be detrimental to my workplace experience (26%)

Whereas the overall population rated ‘not feeling I would be accepted’ (39%) slightly higher than ‘not comfortable enough within myself’ (38%).

Women. Women of diverse sexuality and gender in engineering generally report similar experiences in comparable proportions as the overall population. For example, a large proportion (72%) say that their employee networks feel inclusive of women, and 80% of them agree that having visible out women as role models is important.

Gender Diverse. Engineering respondents with diverse gender identities were as likely as the overall population to report that their employer’s policies or work practices met or exceeded their expectations when asked about visibility of inclusion for gender diverse employees (63%), and alternatives to gendered dress codes (43%). However, gender neutral toilets presented an area where engineering respondents think their employees fell short. Only 31% of trans and gender diverse engineering respondents say that they have the freedom to use the toilets of choice at work, and 19% of them say there is availability of all-gender or gender-neutral toilets, compared with 42% and 28% respectively in the overall population.

Conclusion

It was pleasing to see that although fewer people in engineering identified as LGBTQ+, there are just as many people who support inclusion work as those in the overall population. Likewise, LGBTQ+ people in engineering report a much higher satisfaction with inclusion (visibility, promotion and experience) and executive level advocacy and support. However, like the overall population, a large proportion in engineering are passive allies. All of this points to a considerable number of non-LGBTQ identifying people in engineering who are passive allies and represents a group who are willing to be active allies if given the right understanding and education on the importance of allies and simple ways of being active to make allyship less daunting. Also, senior leaders have an essential role in cultivating a culture of allyship: first, by considering LGBTQ+ inclusion a core part of what differentiates their organisation from others; second, baking D&I principles into all aspects of business, and third, speaking publicly with their own ally stories.

Engineering employees are much less likely to be out in the workplace which is a cause of concern. While we cannot and should not force anyone out of the closet, we know that a quarter of respondents believe that being out will negatively impact their career or work experience, or face rejection in their workplace. Employers cannot afford to be too sanguine in this area – they are not easy issues to remedy. However, we have seen successful shifts in organisations where policies are inclusive, senior management is publicly supportive and workplace culture is positive for all employees. What is changing, we hope, is organisations’ growing awareness that workplace policies, executive leadership and employee resource groups are highly interrelated and that the biggest benefits over time accrue to organisations that balance efforts across all three.

written by Christopher Nelson, Senior Relationship Manager, Pride in Diversity | 2 July 2021

Response rate and respondents

There were 1,217 responses in 2021 from the Insurance industry and 303 people who identified as LGBTQ. The respondents from the Insurance industry are skewed to NSW (41%) and Victoria (23%) and are primarily metropolitan based at 91% which is significantly higher than of all respondents at 81%.

The Insurance industry has a lower population with Bachelor and higher degrees (55%) as compared to the overall at 63%.

GLBTQ inclusivity within the Insurance industry

More than 91% of Insurance respondents support the work that their organisation does for the inclusion of employees with diverse sexualities and genders. This is compared to 85% for all respondents. Likewise, 89% of Insurance respondents think that it is important that employers be active in the area of LGBTQ inclusion, compared to 83% for all sectors.

There is a positive difference regarding visible sign of an organisation’s support for LGBTQ inclusion. In the Insurance industry 84% of respondents acknowledge visible support compared to 78% for all respondents.

There is no significant difference between the Insurance industry and all the employee respondents regarding the tolerance and addressing of jokes and innuendos aimed at LGBTQ people.

When we come to active or passive allies, there also is little difference for the Insurance industry compared to all respondents. Both had a low result for active allies with only 22% stating that they were active allies in Insurance, compared to 20% for all respondents.

Knowledge of active allies in the respondent’s immediate work area was higher in the Insurance industry at 66% compared to 56% for all. Yet there is little difference for knowledge of executive allies in the workplace with 56% in Insurance against only 54% for all employers.

There was little difference in the Insurance industry on what might influence passive allies to become active allies. The higher scores were on how to be an active ally (41%) and more importantly on how to be an active ally when time is limited (43%).

When asked about whether their employer exceeded or met expectations concerning LGBTQ inclusive practices, the Insurance cohort on every statement had a significantly higher rating (5% to 10% and above) on expectations met or exceeded than the responses for all survey participants. These practices included:

- Communication of inclusion initiatives for sexuality and gender diverse employees during the recruitment process (Insurance 61% vs All 53%)

- My experience of inclusion within my immediate work area (Insurance 87% vs All 77%)

- Communication of sexuality and gender diverse inclusion throughout the year (Insurance 80% vs All 68%)

- Overall organisational commitment to people of diverse sexuality and/or gender (Insurance 86% vs All 76%)

- The level of executive endorsement of sexuality and gender diverse inclusion initiatives (Insurance 71% vs All 67%)

- Visibility and promotion of an internal employee network for sexuality & gender diverse employees and allies (Insurance 82% vs All 68%)

- Visibility and promotion of inclusion or ally training regarding sexuality and gender diversity (Insurance 68% vs All 56%)

- Willingness of managers to address negative commentary/jokes that target people of diverse sexuality and/or diverse gender (Insurance 78% vs All 66%)

- Confidential avenues to safely report bullying/harassment related to one's diverse sexuality and/or diverse gender (Insurance 86% vs All 72%)

- Visibility of active allies (Insurance 69% vs All 57%)

Similarly, the Insurance cohort rated the following statements significantly higher (mostly 10% higher) than their other industry cohort.

- I would feel comfortable bringing my partner to work events here (Insurance 89% vs All 79%)

- I would recommend this organisation as an inclusive place to work for people of the same, or similar, sexual orientation and/or gender diversity (Insurance 86% vs All 78%)

- I don't hear jokes/innuendo targeting people of diverse sexuality here (Insurance 80% vs All 70%)

- I don't hear jokes/innuendo targeting people of diverse genders here (Insurance 81% vs All 69%)

- Any jokes/innuendo targeting people of diverse sexuality and/or gender are acted upon quickly here (Insurance 64% vs All 51%)

- Active allies have positively impacted my sense of inclusion here (Insurance 58% vs All 49%)

While the Insurance industry appears more LGBTQ inclusive, the results for acting on jokes and innuendos are still quite low. As is the case of active ally impact on inclusion.

GLBTQ respondents

Moving on to sexual orientation, more Insurance respondents identified as Gay or Lesbian (65%) than for all survey respondents (55%). Identifying as any other diverse sexuality, the Insurance industry was lower than for all survey respondents.

On being out at work regarding their sexual orientation, the Insurance industry respondents were 10% higher in being out to all compared to 51% for all survey respondents, however, this is still quite low.

Being the target of unwanted jokes, innuendo and commentary and the target of serious bullying and sexual harassment is lower in the Insurance industry compared with all respondents. However, feeling safe and supported to report these incidents was significantly higher in the Insurance industry at 91% compared to 82% in other industries.

The reasons for not being out in the workplace had similar rates across the Insurance industry as with all survey respondents, although marginally higher:

- I feel being out at work would be detrimental to my workplace experience

- I feel being out at work would negatively impact my career progression

- I do not feel I would be accepted by some members of my team

One reason for not being out was somewhat different in its responses. With the statement, ‘I am not comfortable enough within myself to be out at work’, 41% of the Insurance respondents agreed or strongly agreed, whereas for all survey respondents the score was 38%. Both scores are very concerning.

The survey responses of being a woman of diverse sexuality and/or gender in the Insurance industry are generally similar to those from the total survey responses, except for the inclusivity of LGBTQ employee networks. Women of diverse sexuality and/or gender in the Insurance industry believe that their employee networks are more inclusive than the norm (76% vs 68%).

The Insurance industry rates higher than the norm on the visibility of inclusion of gender diverse people (74% vs 58%). However, well communicated policies for affirming gender in the workplace were only marginally better than the norm (51% vs 48%). The experiences of being gender diverse or having a trans experience are roughly similar to the norm.

Conclusions

The survey results are positive for the Insurance industry compared to the survey results from all respondents. Like other industries, the Insurance industry needs to do more work promoting the need for active allies in the workplace, particularly executive allies. Although employees of diverse sexuality are more comfortable being out to all, at 51% there is still work to do so that LGBTQ employees can bring their whole selves to work.

written by Nicki Elkin, Senior Relationship Manager, Content Specialist Co-convenor Sapphire Programme, Pride in Diversity | 1 July 2021

The 2021 engagement survey saw a similar number of participants from the Pharmaceutical industry as 2020, with 330 survey respondents from organisations working in this area (approximately 50% also participated in the survey in 2020). The analysis does not include those professionals employed in other industries or sectors. Of these, 32 participants identified as being part of the LGBTQ community (10.1% vs 18.8% of the national cohort).

In regard to the demographic segmentation of the survey participants, this industry differs from the national mix in a number of significant areas:

- The industry is highly centralized into NSW (62% compared to 30% of the national cohort)

- Has more representation of women (66% vs 54%) *

- Has no respondents who self-identified as having a non-binary gender (vs 1.3%)

- Has more employees with bachelor and post-graduate degrees (85% vs 64%) *

- Over-represented by people working in city/metro areas (94.3% vs 81.1%) *

- Over-represented by people in senior management positions (16.4% vs 7.5%) *

- The industry also appears to be under-represented by Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islanders, people living with disabilities, neurodiverse people, and mature age employees, and over-represented by people of colour and people of faith/religion.

There were also some significant differences in the personal views of LGBTQ people within the industry. While the numbers of participants raised in an environment where same-sex relationships or gender diverse people were not easily accepted is similar (49.8% vs 48.7%), and as is the numbers of participants who believe romantic relationships between people of diverse sexuality and/or gender are just like any other (89.5% vs 87.9%), the number of participants who believe there are more than two genders is significantly higher (64.5% vs 54.6%).

When you look at the state of LGBTQ workplace inclusion, the survey indicates that the pharmaceutical industry is performing well compared to the national cohort. In nearly all the key questions within the survey, the participants indicate better performance than the national results.

Some of the most pronounced differences include:

- 95% of total respondents in the industry support the work their organisation does for the inclusion of employees of diverse sexuality and/or gender (vs 85% nationally)

- 91% think it is important that employers be active in this area of diversity & inclusion (vs 83%) and 92% believe this work has a positive influence on organisational culture (vs 82%)

- 71% of total respondents in the industry thought an organisation’s positive track record in this aspect of inclusion would positively influence them to join the organisation (vs 59% nationally)

- 93% thought that initiatives in this area have been regularly communicated during the year (vs 75%)

- 90% have heard their executive leaders speak positively about this aspect of diversity & inclusion (vs 71%)

- 80% stated that awareness or ally training was made available throughout the year (vs 59%) and 66% had attended such training (vs 35%)

- 71% claimed jokes and innuendo were called out and addressed (vs 58%)

- Only 7% of total respondents have witnessed negative behaviours/mild harassment (vs 14%) and 2.5% have witnessed serious bullying (vs 5.3%) targeting LGBTQ people

Health and wellbeing indicators were higher than average:

- 90% of total respondents feel mentally well at work (vs 78%)

- 90% feel they can be themselves at work (vs 81%)

- 90% feel a sense of belonging (vs 77%)

Business case indicators were also more positive with 94% of participants feeling productive (vs 88%) and 93% feeling engaged (vs 81%).

In regard to active allies, the industry exceeds the national profile, despite there being fewer LGBTQ respondents (LGBTQ people are twice as likely to be an active ally than non-LGBTQ); 33% of respondents would describe themselves as active allies (vs 23%), and consequently allies are for more visible within this industry:

- 82% of total respondents know of active allies within their immediate work area (vs 56%)